A Practical Guide to Vacuum Components for Reliable (U)HV

Expertise

You want a vacuum system that behaves like an engineered system, not a mystery. Specifically, you want:

- Predictable pump-down to target pressure

- Stable base pressure with no unexplained drift

- Hardware that survives bakeout and thermal cycling

- No last-minute leaks before qualification, experiments, or delivery

You are not chasing theoretical limits. You are chasing repeatability. When the system is assembled correctly, it should behave correctly, every time.

Vacuum systems rarely fail because of one catastrophic mistake. They fail because of small, compounding technical decisions.

Common obstacles include:

- Leaks that appear only after bakeout or thermal cycling

- Long, inconsistent pump-down times

- Pressure drift that cannot be traced to a single component

- Virtual leaks from trapped volumes and blind holes

- Different results depending on who assembled the system

These problems consume time, erode confidence, and turn vacuum into a bottleneck instead of an enabler. The role of Tactile is simple:

- Translate vacuum physics into practical component choices

- Highlight failure modes before they appear

- Reduce assembly-dependent variability

- Help vacuum performance become repeatable and boring

Choosing the correct Vacuum Components

1. Vacuum Regime Comes First

Every component decision flows from one question: What vacuum level must this joint support, consistently, over time?

- High Vacuum (HV): elastomers acceptable, permeation tolerated

- Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV): metal seals required, outgassing dominates

- Bakeout required: eliminates most elastomers by default

If this is not defined first, every downstream choice becomes risky.

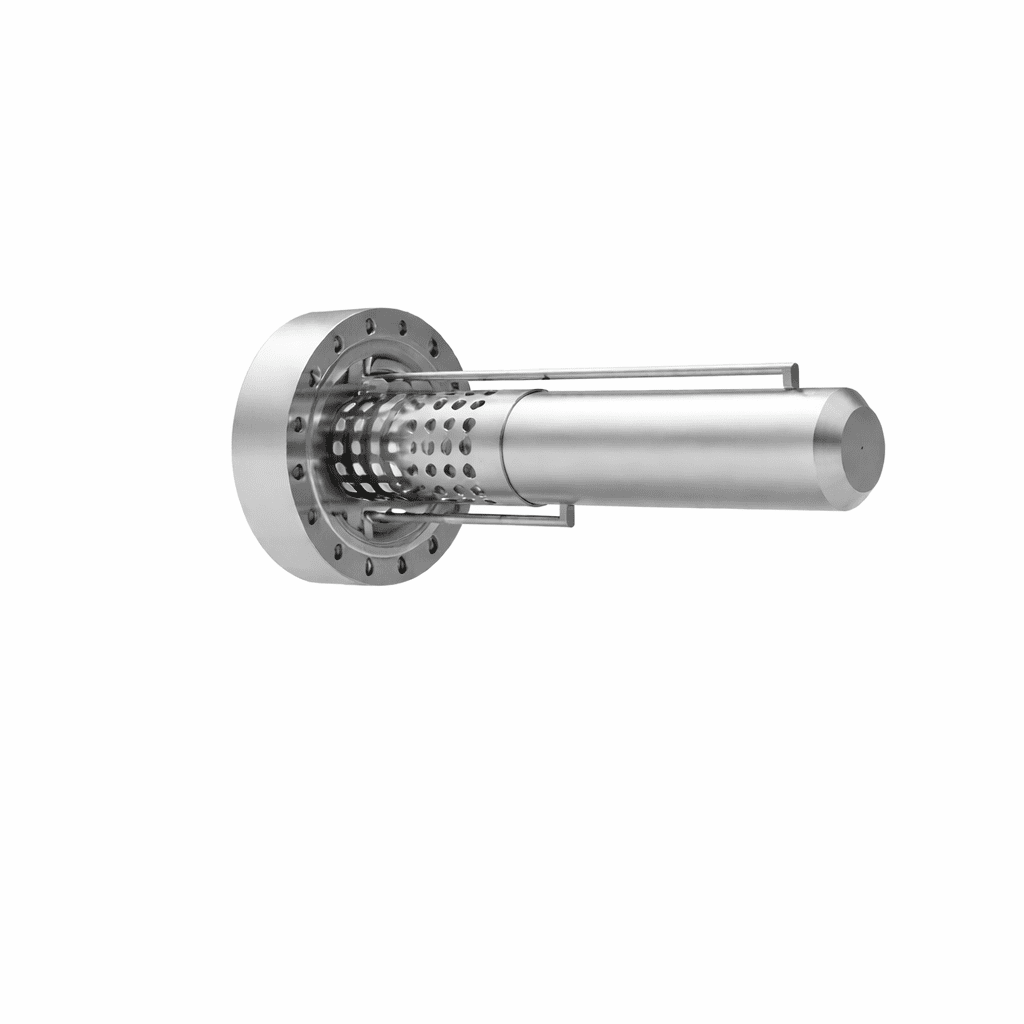

2. Sealing Systems: Where Vacuum Is Won or Lost

KF / ISO (Elastomer Seals) Best for:

- HV systems

- Frequent access

- Load locks and service ports

Limitations:

- Permeation sets a pressure floor

- Temperature limits restrict bakeout

- Aging and compression set introduce variability

CF (Metal Seals) Best for:

- UHV systems

- Bakeout and thermal cycling

- Long-term stability

Key rules:

- Metal gaskets are single-use

- Knife edges must be pristine

- Bolt torque and sequence matter

A system that needs stability after bakeout should default to metal seals.

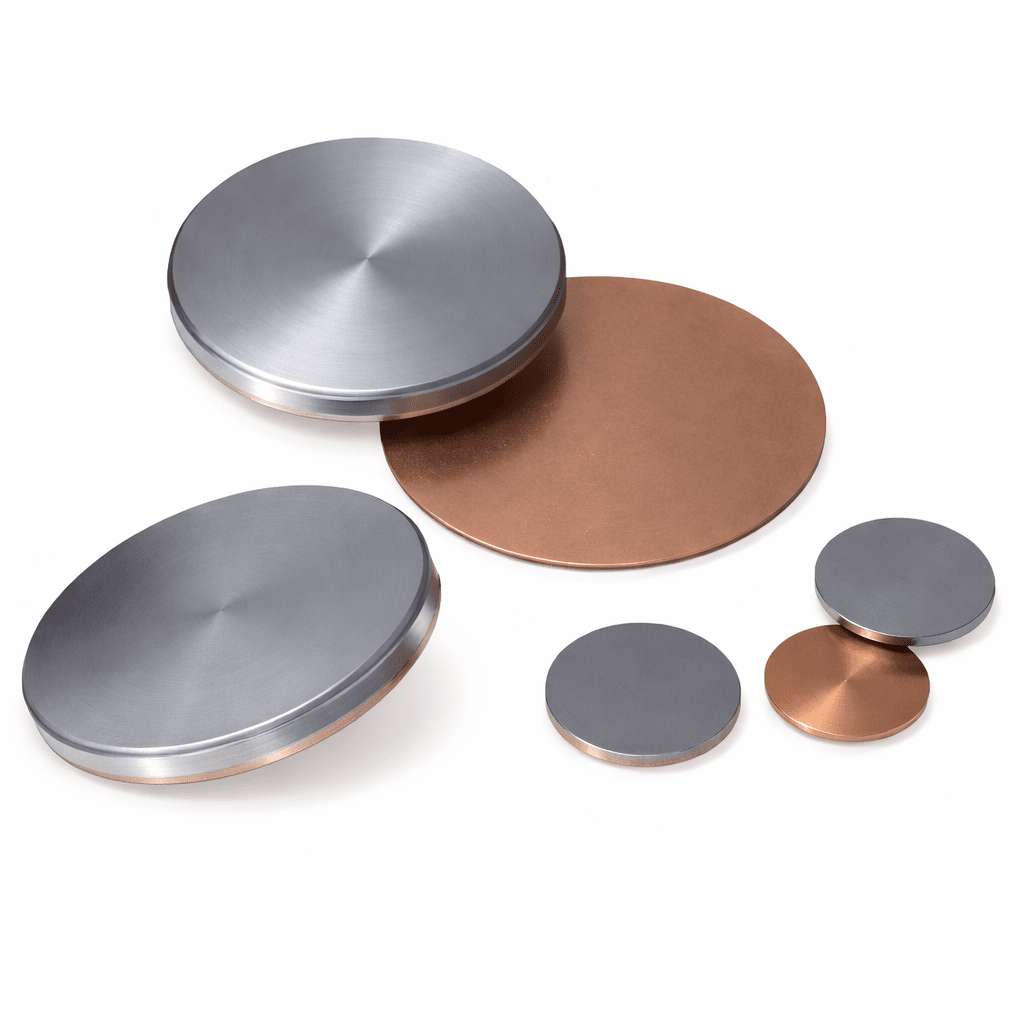

3. Materials: The Chamber Is the Gas Source

At UHV, you are no longer pumping gas from the volume, you are pumping gas from the walls.

Common structural materials

- Stainless steel: default choice, robust, weldable, predictable

- Aluminum: low outgassing, lightweight, non-magnetic

- Titanium: premium choice for lowest hydrogen contribution

Avoid:

- Plastics and polymers inside vacuum volumes

- Plated or painted surfaces

- Zinc-containing alloys

Material purity, surface finish, and cleaning matter more than bulk strength.

4. Trapped Volumes and Virtual Leaks

Many “mystery leaks” are not leaks at all. They are trapped gas reservoirs that empty slowly.

Common sources:

- Blind tapped holes exposed to vacuum

- Unvented screws and bolts

- O-ring grooves without vent paths

- Internal cavities and dead ends

Best practices:

- Use vented fasteners

- Eliminate blind holes where possible

- Vent unavoidable cavities deliberately

- Simplify internal geometry

Virtual leaks do not show up in helium tests, they show up in pump-down curves.

5. Assembly Discipline Is a Design Variable

Most chronic vacuum problems are human-factor problems. Key assembly rules:

- Clean all sealing surfaces immediately before assembly

- Wear clean, lint-free gloves

- Never slide gaskets across sealing faces

- Tighten bolts incrementally in a cross/star pattern

- Use torque tools where specified

- Support heavy components to avoid flange distortion

If assembly varies, vacuum performance will vary.

Our Approach

- 1 Define the Environment Vacuum regime, temperature, bakeout, cleanliness requirements.

- 2 Specify the Hardware: Materials, sealing method, geometry, tolerances, nothing assumed.

- 3 Confirm Before Ordering: Review the full specification and remove ambiguity.

- 4 Deliver Ready to Install: Clean, compliant, documented, and predictable.

Each step reduces risk before it compounds.

Nothing is assumed: all vacuum, thermal, and mechanical requirements are confirmed before anything is ordered, so there are no hidden risks or surprises. You stay in control at every step with clear standards, full transparency, and final approval before release, no unnecessary complexity, only what truly matters for your system to perform reliably.

Get a quote at info@tactile.tools or Start Your Vacuum Hardware Specification

Success is not extreme pressure numbers. Success is calm, repeatable behaviour.

- Pump-down behaves the same every time

- Base pressure stays stable after bakeout

- Qualification runs proceed without surprises

- Hardware choices are intentional and documented

We want to replace second-guessing with confidence, eliminate pre-run stress, and return your focus to real engineering instead of constant troubleshooting.

A vacuum system should behave like an engineered system, not a mystery. When it does, vacuum fades into the background.

Tactile purpose is to remove uncertainty from vacuum systems, helping engineers move from hidden instability to predictable performance, calm operations, and confidence in their results.